Orsted, the Danish renewable energy giant, has warned that it may write off as much as $2.12 billion because of supply chain problems and other issues at three giant offshore wind installations off the United States’ East Coast.

The announcement from the company, which has been a global pioneer in offshore wind energy, is the latest sign of trouble in an industry expected to supply an increasingly large portion of clean energy to meet the climate-change goals of many countries, including the United States.

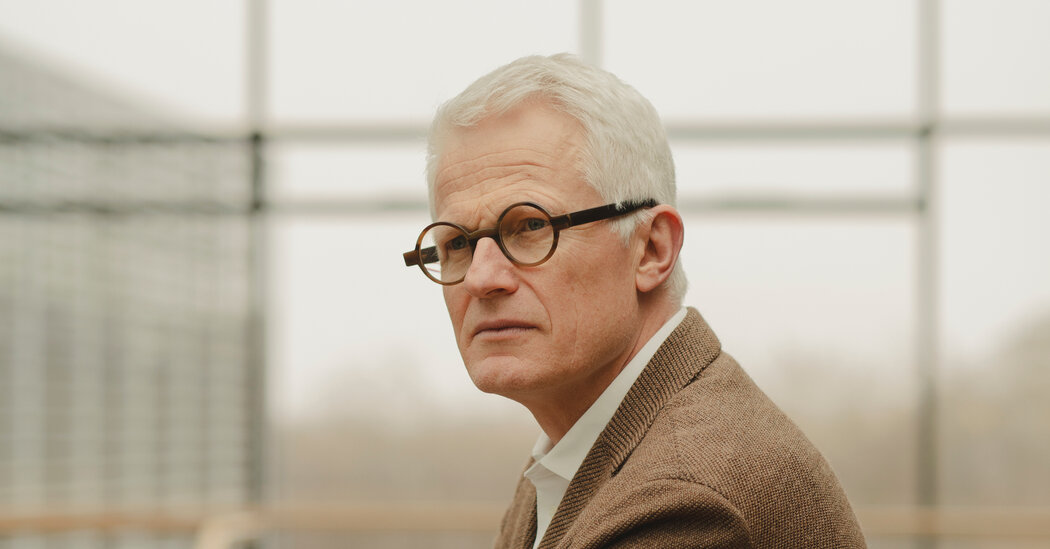

“This will not be the last that we will see this year,” said Soeren Lassen, the head of offshore wind at Wood Mackenzie, a consulting firm.

Orsted’s shares tumbled 25 percent after the news.

The wind farms covered in the announcement would supply power to customers in New York, Connecticut and New Jersey. Orsted also said it would reconfigure plans for two other projects to avoid similar problems.

The company said the projects were being hit by delays to suppliers and contractors, like wind turbine component manufacturers and the specialized ships needed to install the large machines, whose blades are as long as football fields.

“There is a continuously increasing risk in these suppliers’ ability to deliver on their commitments and contracted schedules,” Orsted said in a statement on Tuesday.

Orsted said such delays could lead to extra costs and slower-than-anticipated receipts of revenues from the power generated by the turbines. It also said that at this point, it would continue to perform preliminary work on building the wind farms — although walking away was an option.

“We are willing to walk away from projects if we do not see value creation that meets our criteria,” Mads Nipper, Orsted’s chief executive, said on a call with analysts on Wednesday, according to an unofficial transcript.

The company said the sharp rise in interests rates would also increase costs in the United States. Renewable energy projects require billions in investment upfront. Orsted also said it might not be able to achieve tax credits from the United States as large as it had anticipated.

The impairments amount to about half of the $4 billion that Orsted said it had invested in its offshore portfolio in the United States but are only a fraction of the estimated overall cost of these projects, which is more than $10 billion, and the company’s overall American plans.

Orsted owns a small operating wind farm off Rhode Island and is developing seven others off the East Coast, according to the company’s website.

While other companies have abandoned some contracts to supply power or threatened to, Orsted has so far said it does not wish to. The United States remains an important future market for the company and other developers. On the call with analysts, Mr. Nipper said giving up on these projects would not be the right thing for shareholders at this time.

The offshore wind industry, which has been developed in countries like Denmark, Britain and Germany in recent decades, has won favor with governments and investors looking to place large sums in clean energy.

Large arrays of turbines with the capacity of conventional power-generation plants can be built at sea, where winds are stronger and steadier than on land. In Europe, at least, there is also less opposition to planting towers with enormous spinning blades offshore than installing them on farms or hillsides.

After rapid growth, the industry has recently been upended by a variety of factors including manufacturing and logistics delays from the pandemic and inflation, which has drastically changed the economics of projects that can take a decade to move from the drawing board to an operating wind farm.

In a potential indication of a souring on prospects for offshore wind in the United States, an auction of wind lease areas in the Gulf of Mexico on Tuesday produced disappointing results, attracting just two bidders.

Mr. Lassen of Wood Mackenzie said that the United States was a new market for the offshore wind industry and that delays were not surprising. The network of suppliers for offshore wind in the United States is in its infancy, and vessels used to install the big turbines must be brought from Europe, adding to costs and delays. One reason for the disappointing talks on taxes may be that developers cannot find enough suppliers to meet rules for using locally based goods and services, analysts say.

Mr. Lassen said that while early delays might be expected, a major risk was that they would cascade, frustrating efforts to make offshore wind a key source of electric power in the United States and elsewhere.

“They want policymakers to recognize the issues that the industry is facing,” he said.