This week, Mayor Eric Adams released proposed guidelines for Local Law 97, trailblazing climate legislation that limits fossil fuel emissions from the large buildings that produce about 70 percent of greenhouse gases in New York City.

Not everyone was happy with the proposed rules. Much of the criticism was focused on an option that would allow buildings to apply for a two-year, fee-free extension if they would not be in compliance by the time the law goes into effect on Jan 1.

Some environmental activists oppose the extension, saying it gives the real estate industry a loophole to delay urgent climate reform. On the other side of the issue, some building owners and residents feel two years is not enough time to enact repairs that could cost millions of dollars. The law, passed in 2019, set a series of deadlines for buildings to reduce emissions by certain amounts, but the city’s Department of Buildings had not updated the rules around the law since last year. The first deadline is 2024.

To qualify for the two-year extension, applicants must show “good faith efforts” to reduce emissions, a term that some opponents and supporters of Local Law 97 both say is too vaguely defined. The public may comment on the new rules until Oct. 24, after which they become law.

“This is a disaster,” said Pete Sikora, who was on the advisory board for Local Law 97 and serves as the climate and inequality campaigns director of New York Communities for Change, a nonprofit organization. Loosening the rules, he said, “endangers a huge job-creation and pollution-reduction set of policies.”

The law targets some of the city’s biggest producers of greenhouse gas emissions, which are disrupting weather patterns and raising sea levels: about 50,000 properties of over 25,000 square feet. So far, close to 90 percent of these buildings are in compliance for next year. The next deadline, in 2030, calls for stricter limits: a 40 percent cut in emissions. By 2050, zero emissions is the goal. Violators face potentially steep penalties.

City Councilman James F. Gennaro, a Queens Democrat who heads the council’s Committee on Environmental Protection, Resiliency and Waterfronts, said the “good faith efforts” option was a helpful compromise between the goals of Local Law 97 and the potential cost of compliance.

“The two-year extension is a very effective way for the administration to hold people accountable and also to understand the burdens that this places on real estate owners, many of whom are co-op operators and shareholders who live in the outer boroughs and face significant challenges in coming into compliance,” he said.

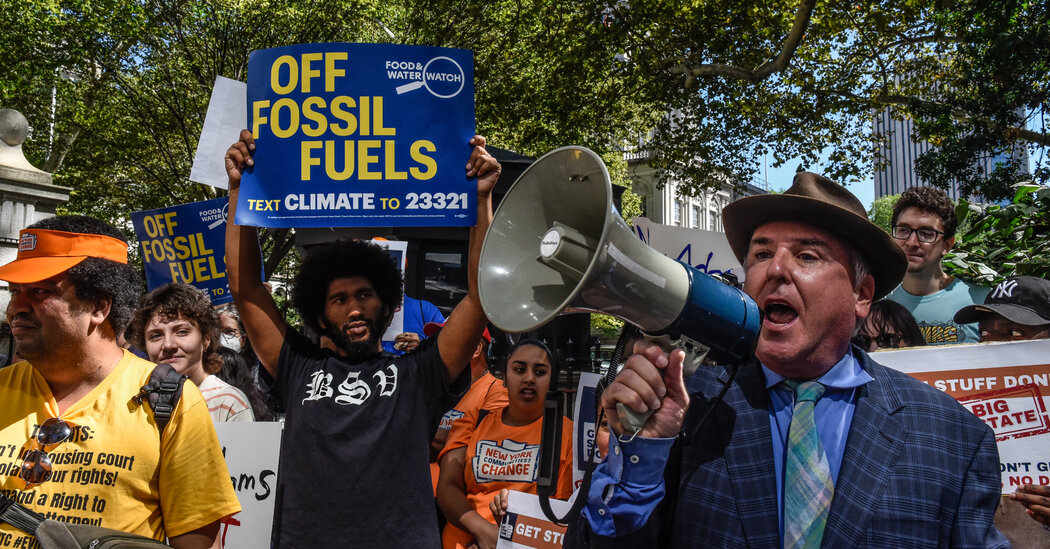

At a protest outside City Hall on Thursday, Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso criticized the new rules, including the two-year delay and an option to buy offsets. “We should be doubling down on legislation like this, not weakening it,” he said.

The two-year option “is a big, big loophole” for the real estate industry, Mr. Sikora said in an interview. “They’ve had five years, since the law passed in 2019, to achieve a pretty loose limit,” he said, referring to the modest emissions target for next year.

Applicants seeking the “good faith” exemption must obtain permits, approved by the city, that outline decarbonization and energy-saving plans.

Rohit T. Aggarwala, the city’s chief climate officer, defended the new rules, saying that the “good faith” option gets buildings engaged in decarbonization efforts and prepares them for the much tougher 2030 deadline.

“What we have done very intentionally is say if you are late on 2024 targets, you can go ahead and pay the fees, or you can enter into a legally binding agreement with the city,” he said. This agreement, he said, will initiate an agreed-upon plan for reducing emissions.

A spokesman for the Real Estate Board of New York said the organization, a trade group that represents the city’s building owners and developers, remained committed to the law and was reviewing its rules, as it takes into consideration “the financial penalties still on the horizon for many buildings next year and tens of thousands more in 2030.”

Meeting the law’s emissions limits, however, tends to be easier for larger commercial buildings than for residential buildings, many of which are fueled by oil and gas. Co-op residents in large, aging buildings are particularly worried about Local Law 97’s deadlines and the potential cost of compliance.

Jane Menton, who is on the board of a co-op in Sunnyside, Queens, said that the city should focus first on large infrastructure projects, like expanding the capacity of the electrical grid while it switches to clean energy sources, before asking residential buildings to decarbonize.

An engineer recently conducted a study of Ms. Menton’s 158-unit building and concluded that replacing the property’s fossil fuel system with electricity would cost $3 million. The engineer could not predict how long the work would take, Ms. Menton said, and his report stated that such a project was “not recommended at this time.”

Bob Friedrich, the board president of Glen Oaks Village, a 10,000-resident garden co-op in northeastern Queens, plans to apply for the “good faith effort” extension, but said he was confused about whether the rule will take into account energy-reducing efforts that have already been made, like the 18,000 energy-efficient windows Glen Oaks installed five years ago, which cost $6 million.

According to the Department of Buildings, projects that were completed in 2013 or later that resulted in at least a 10 percent reduction in emissions for a building must be included in “good faith” submissions, along with other retrofit plans to meet emissions targets.

Mr. Friedrich, who supports legislation that would give buildings seven years to comply with emissions standards and is part of a lawsuit to prevent the enforcement of Local Law 97, said he was impressed that the proposed rules focused on funding opportunities like tax abatement programs to help building owners who would otherwise have to take on debt, because “loans don’t do it.”

There is also concern over renewable energy credits, or RECs, which can be purchased under Local Law 97 to offset emissions, and would fund alternative energy projects like solar and wind. Whereas Mr. Sikora would like to see the use of RECs restricted, Mr. Friedrich would like the opportunity to purchase them. But according to the recently released new rules, if he applies for the “good faith effort” extension, he won’t be able to.

“I’m really shocked that the mayor allowed that provision to be put in,” Mr. Friedrich said. Mr. Sikora, too, said he was shocked, but for a different reason. He said he had been dismayed to discover that an advisory board recommendation to tighten limits on credits, so that they could be used to cover only 30 percent of a building’s excess emissions, did not end up in the rules package, even though it had the support of 26 City Council members.

The City Council can override the proposed rules after the 30-day comment period, but “it’s going to be a fight,” said Carmen De La Rosa, a Council member who represents Washington Heights and supports stricter limits on purchasing renewable energy credits.

Mr. Aggarwala, the city’s chief climate officer, said there will be no renewable energy credits available until 2026, which is when New York City’s grid is scheduled to start connecting with green energy for the first time. Until then, he said the focus should be on “mobilizing $12 to $15 billion of work over the next seven years” in order to be ready for 2030.

“The law’s working,” said Daniel Zarrilli, a special advisor for Climate and Sustainability at Columbia University, who was instrumental in passing the legislation. “I just hope that the city is crystal clear that the 2030 goals are not up for debate.”