Gov. Gavin Newsom of California said on Sunday that he would sign a landmark climate bill that passed the state’s legislature last week requiring major companies to publicly disclose their greenhouse gas emissions, a move with national and global repercussions.

The new law will require about 5,000 companies to report the amount of greenhouse gas pollution that is directly emitted by their operations and also the amount of indirect emissions from things like employee travel, waste disposal and supply chains.

Climate policy advocates have long argued that such disclosures are an essential first step in efforts to harness financial markets to rein in planet-warming pollution. For example, when investors are made aware of the climate-warming impacts of a company, they may choose to steer their money elsewhere.

The law would apply to public and private businesses that make more than $1 billion annually and operate in California. But because the state is the world’s fifth-largest economy, California often sets the trend for the nation, and many of the affected businesses are global corporations.

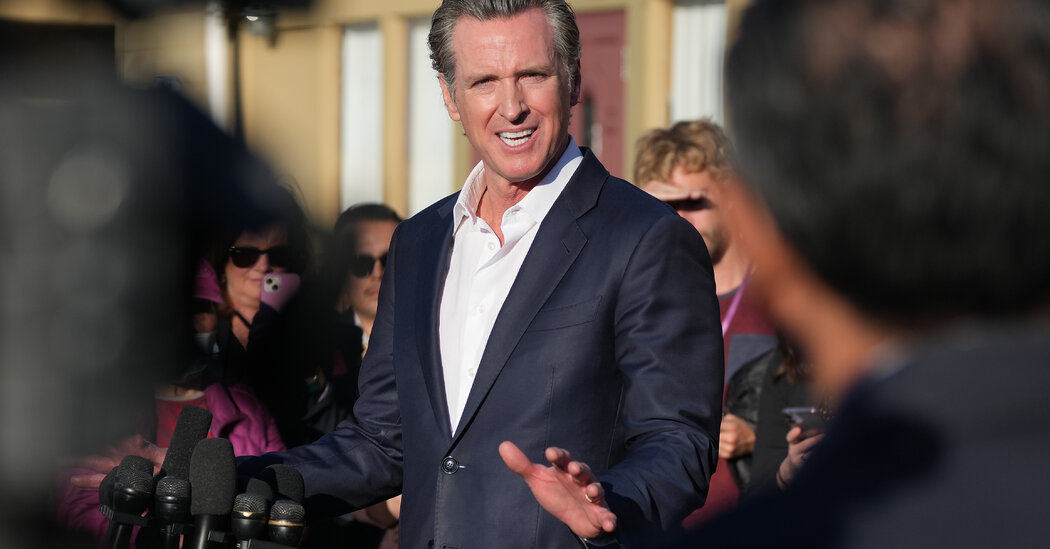

There had been some question as to whether Mr. Newsom, a Democrat who has pushed for some of the nation’s most ambitious policies to fight climate change, would sign the legislation. The California Chamber of Commerce lobbied against it, and the governor’s own state finance department was opposed, saying the measure would result in new costs that are not currently in the state spending plan. After the bill cleared the State Senate last week and was sent to Mr. Newsom’s desk, his office declined to say what he would do.

But asked at a Climate Week event at the Times Center on Sunday if he would sign the bill, Mr. Newsom responded first by detailing California’s history of vanguard climate policies, including his own administration’s requirement that every new car in the state be all-electric by 2035.

“Would I cede that leadership by having a response that is anything but, Of course I will sign that bill?” he said in response to a question from David Gelles, a New York Times reporter who interviewed the governor before an audience. “No, I will not.”

Mr. Newsom said that his signature came with “a modest caveat” that his office wanted “some cleanup on some little language” in the legislation. But he did not clarify the changes that he wished to make, and a spokesman for his office did not respond to a voice mail message or text message seeking an answer.

Many of the affected businesses would include oil and gas giants like Chevron, major financial institutions like Wells Fargo and global brands like Apple. The companies would be required to disclose all their emissions starting in 2027.

The new measure would be paired with another new law that requires companies with revenue over $500 million to report their climate-related risks, although they would not have to disclose their specific emissions.

The California legislation goes beyond a measure proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, which would require only publicly-traded companies to disclose their emissions. That proposal, which has yet to be finalized, is facing strong opposition from conservatives and business groups.

“The fact that a single state like California would do this is both potentially troubling and potentially promising,” Robert Stavins, director of the Environmental Economics program at Harvard, said. “It could be the case that a company that is valued at $1 billion has $35 of activity in California but is nevertheless affected. But it’s potentially promising because we have such a long history in the U.S. of California being out front on environmental regulation and other states following and the federal government eventually catching up.”

Climate policy advocates praised the move. “These two first-in-the-nation bills will provide unprecedented insight into corporate climate emissions and financial climate risk,” said Mindy S. Lubber, chief executive and president of Ceres, a nonprofit group that works with investors and companies on environmental issues.

Opponents said that compliance would be expensive and onerous, particularly the requirement that businesses accurately track and measure all emissions. For example, clothing manufacturers worry that they would have to report the emissions associated with growing, weaving and transporting textiles, in addition to reporting the direct emissions from their garment manufacturing plants.

The California Chamber of Commerce last week called the legislation “a costly mandate that will negatively impact businesses of all sizes in California and will not directly reduce emissions,” Denise Davis, an executive vice president at the California Chamber of Commerce, said.

Ms. Davis said on Sunday that her organization was disappointed by Mr. Newsom’s decision but was hopeful that further “cleanup” legislation next year could mitigate the impact of the new law.